History

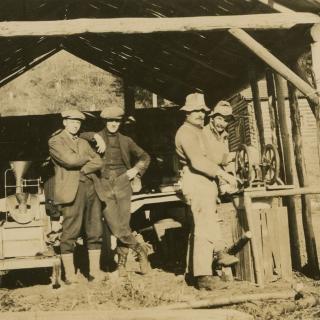

Cowboy Jim McConnel in the Chilcotin | Museum of the Cariboo ChilcotinCariboo History

A braided story of First Nations, fur trading, the Gold Rush and ranching weaves the history of the Cariboo to life. The story of the South Cariboo is written in the numbers signposted along Highway 97’s original roadhouse towns. About every 21km/13mi along this historic 644km/400mi route, a roadhouse was located. Travellers could journey its entire length by stagecoach in four days, providing they could afford $130 for a one way ticket. Today, Hat Creek Ranch is one of the Cariboo’s largest surviving roadhouses, just 11km/7mi north of Cache Creek amid rolling, sagebrush hills at the junction of Highways 97 and 99. This B.C. Heritage Site marks the crossroads where all major threads of the South Cariboo’s compelling history – fur trading, ranching, First Nations culture and gold – intersect. Most of the roadhouses are long gone, while a few have evolved into villages and towns where modern-day travellers can still trace the region’s gold rush past through a landscape that appears airlifted out of an old western. Prospectors and merchants ventured to the Central Cariboo in 1859 after the news of a big gold strike on the Horsefly River, 65km/40mi east of Williams Lake. The following year, William Pinchbeck, a tough police constable from Victoria, arrived to keep law and order; juggling jobs as lawyer, judge, and jailer while building a homestead and rest house with restaurant, saloon, general store and race-horse track. Race days attracted hundreds of spectators, including one memorable contest in 1861 when the stakes were a whopping $100,000. Pinchbeck was a busy man, his roadhouse, already famous for its White Wheat Whiskey (from his own distillery at 25 cents a shot), suffered no lack of business and he came to own almost the entire Williams Lake River Valley. Pinchbeck’s grassy gravesite above his former ranch is one of the most famous in the Cariboo, overlooking the Williams Lake Stampede Grounds. The Cariboo Gold Rush of the 1860s came to an end about a decade after its start, and its prospectors fled. With paddle-wheelers plying the Fraser River and interior lakes, and a major railway to come, the region’s newly settled farmers and ranchers stayed on. Soon a new wave of modern-day adventurers followed, seeking their own golden dreams in the North Cariboo, a region as rich in untapped wilderness as it once was in gold. To the northeast of Quesnel, the Blackwater River is the eastern entry point of the Nuxalk-Carrier Grease Trail (Alexander Mackenzie Heritage Trail). Extending 420km/261mi westward to the Pacific, this historic trail was once the Nuxalk (new-hawk) and Carrier First Nations’ primary trade route. Here in 1793, famed explorer Alexander Mackenzie traced its unmapped terrain to become the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean by land.

Chilcotin History

Unlike the Cariboo, the Chilcotin was never invaded by swarms of gold crazed prospectors, so developed much differently. It’s a world of few roads, little industry and pockets of people, the majority being First Nation. It has an impressive diversity of wildlife, including Canada’s largest population of bighorn sheep, rare white pelicans, trumpeter swans, bears, lynx, wolves, mountain caribou and hundreds of wild horses. This makes it the perfect place for anyone wanting to explore the pristine Canada of their imagination. Nothing reflects the spirit of the region more than the completion of Highway 20, at one time known as the Freedom Road, because its completion freed up access to the central coast. Until 1953, the road ended at Anahim Lake, 137km/85mi short of Bella Coola on the coast because the provincial government refused to extend it – claiming the mountainous terrain was too difficult. So, local volunteers working from opposite ends with two bulldozers and supplies purchased on credit finished the job. This determination and independent spirit remains in the fabric and character of the Chilcotin and Coastal residents today. The rustic road was not really considered a highway when first completed, but it was enough to convince the government to take over maintenance and improvements in 1955. Those who settled this isolated region had to be tough – like Nellie Hance, who, in 1887, became the first white woman to travel into the Chilcotin by journeying 485km/301mi riding side saddle on horseback to reach her husband Tom’s trading post near Lee’s Corner (also known as Hanceville). Others were not only tough but, perhaps, a little crazy. Rancher Norman Lee, after whom Lee’s Corner was named, set out from his spread in May 1898 with 200 head of cattle on a 2,500km/1,553mi trek to the Klondike goldfields. None of his cattle survived the journey, but Lee did, arriving in Vancouver five months later with a roll of blankets, a dog and one dollar. Borrowing enough money for the train to Ashcroft and a horse to ride home, Lee was soon ranching again and by 1902 was well on the way back to prosperity. His descendants are still ranching in the Chilcotin today. As white settlers arrived, most of the First Nation Chilcotin chiefs were friendly and cooperative, particularly when treated with equality and respect. Many of the First Nations worked with settlers as ranch hands, cowboys, packers and guides. Others started their own freight companies using teams and wagons, or homesteaded ranches while their wives sewed and sold moccasins and gloves made from tanned deer and caribou hides, and robes made from marmot fur.

Coast History

The Norwegian explorer, Thor Heyerdahl, became famous for his expeditions in and across the South Pacific. But, well before this fame, he explored British Columbia’s central coast extensively, researching the lifestyles and origins of the indigenous people who live here. As a result of his investigation, he was later able to theorize about similarities among the British Columbian First Nations people and those who lived on far-removed Pacific islands. That gave rise to his theories – and later explorations – about indigenous peoples around the Pacific having related roots. Even though his theories were never accepted by anthropologists, Heyerdahl’s life’s work began in the inlets, islands, and mainland of this craggy coastline and directly led to his legendary explorations. Of course, Heyerdahl wasn’t the first non-native person to explore these shores. In 1793, an intrepid 29-year old Scotsman named Alexander Mackenzie – accompanied by seven French Canadian voyageurs and two First Nations porters – paddled into the Dean Channel near present-day Bella Coola. That event completed the first crossing of North America to the Pacific. Before returning east, the explorer scrawled an inscription on a rock using a reddish mixture of bear grease and vermilion: ‘Alex Mackenzie, from Canada, by land, 22nd July, 1793.’ That rock still bears his words, permanently inscribed by surveyors who followed. The highway through the Bella Coola Valley parallels the ancient trading route, or ‘grease trail’, taken by Alexander Mackenzie on his way to the sea in 1793. Long before Mackenzie’s arrival, the Nuxalk (nu-halk) people thrived here alongside the salmon-filled rivers. The valley was part of a trade corridor between coastal and interior native groups, where furs and leather were exchanged for salmon and eulachon (oo-lick-an) oil. The oil was obtained from the rendered fat of the small herring-like fish that was valued for its calories and vitamin content. It was then transported along the ‘grease’ trails. The landscape northwest of Bella Coola is some of the most isolated in the province. Across a 3,000,000hec/7,413,160ac area that lies within the Great Bear Rainforest remains the largest tract of unspoiled temperate rainforest left in the world. Several ancient First Nations cultural sites can be found here, as well as a striking array of wildlife, including the Kermode (or Spirit Bear), a rare, white-coated variation of the black bear that is sacred to B.C.’s First Nation people. Explorers from Russia, Britain, France, and Spain also came to this region in the last quarter of the 18th century, motivated by the chance of trade, although Spain was here to protect its then territorial waters. Getting here by ship is much easier now than in either Mackenzie or Heyerdahl’s time. Ports of call may include Bella Bella, McLoughlin Bay, Shearwater, Klemtu, Ocean Falls, and the Hakai Pass.

Accommodations and Activities in History

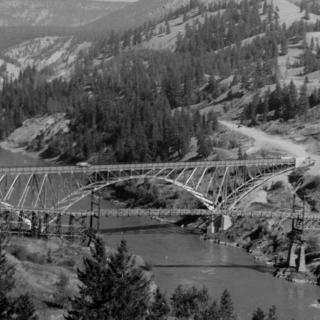

Bailey Bridge Campsite and Cabins

Located in beautiful Bella Coola and inspired by the surrounding landscape. Bailey Bridge Cabins, Campsites, RV Hook Ups are designed to make your visit unique, comfortable and a fun experience. Call us today or complete our contact form with your…

Barkerville Historic Town & Park

Welcome to the Granddaddy of them all - Barkerville Historic Town & Park - the final destination on the Cariboo Waggon Road. In 1862, Billy Barker struck gold in this area of the Cariboo and 150 years later, the town…

Barney's Lakeside Resort

Come experience the peace and quiet of the Chilcotin our motto is "Get away from it all” unwind, unplug - it's stress-free. Come fishing for Kokanee and wild Rainbow Trout, an abundance of wildlife, hiking trails and unlimited 4×4 and…

Big Bar Guest Ranch

Weyt-K! Big Bar Guest Ranch is proudly owned by the Stswecem'c Xgat'tem First Nation. Here you will find traditional indigenous experiences interwoven with the day to day ranch life of a wrangler. Nestled in the heart of our Stswecem'c Xgat'tem…

Bralorne Pioneer Museum

Travel through time back to the booming gold rush era in the Bridge River Valley at the Bralorne Pioneer Museum. In their heyday, the Bralorne and Pioneer mines were two of the wealthiest mines in Canada attracting people from all…

Cariboo Chilcotin Jetboat Adventures

Cariboo Chilcotin Jetboat Adventures offers tours 15 minutes west of Williams Lake BC. Tours begin in May and end in October. We offer day trips and multi day trips showcasing beautiful river scenery, Indigenous culture sharing experiences, gold rush history…

Chilcotin River Trading

First Nations owned and operated full-service gas station that offers regular, premium, and diesel at all 6 pumps. The store also offers a card lock for businesses and semi trucks. Come try the best local grilled sandwiches in the West!…

Copper Sun Gallery

Copper Sun Gallery is located on the traditional Nuxalk territory in beautiful Bella Coola, B.C., offering handcrafted Nuxalk art made locally. You'll find that the art and jewellery from this region has its own distinct style unique to the Nuxalk…

Copper Sun Journeys

Journey through the Great Bear Rainforest with knowledgeable Indigenous guides. Tour Nuxhalk territory's spectacular scenery, abundant wildlife and dramatic mountain peaks as you learn the history and stories of this beautiful region. Discover the stories behind ancient petroglyphs, tour old-growth…

Fawn Lake Resort

We are located 4km off Highway 24 in a quiet wilderness setting; only electric motors are permitted on Fawn Lake. We offer charming lakefront log cabins & RV/campsites with 15A power & water. Pets are very welcome. Amenities include motorboat,…

Frog On The Bog Gifts

A really unique gift store in Wells, with over 20 lines of products from regional and local craftspeople, and an eclectic mix of souvenirs, clothing, handmade leather products, books and more. Our motto is, "If you think you've seen it…

H'aiagal'ath Grizzly Bear Tours Inc.

For the W’ui’kinuxv (O-wik-en-o), stewardship is a shared responsibility with Grizzly Bears, who are the keepers of the land. The vast wilderness in the Central Coast region of British Columbia is W’ui’kinuxv Territory. For more than 14,000 years, the W’ui’kinuxv…

Haylmore Heritage Site

The Haylmore Heritage Site is the homesite of Will Haylmore, Deputy Mine Recorder during the Cariboo Gold Rush. The Bridge River Valley was one of the richest gold producing areas between 1930-1950, and there are lots of amazing history to…

High Country Inn

Located in the quaint rural community of Likely, High Country Inn is situated on the sunny side of the valley overlooking Quesnel Lake. Our well maintained rooms come with satellite TV, internet, fridge and all the comforts one would need…

Historic Chilcotin Lodge

The Lodge is located in Riske Creek on the Chilcotin Plateau, not far from the confluence of the Fraser and Chilcotin Rivers. It is also close to both the Junction Sheep Range Park which contains a large herd of California…

Historic Hat Creek

Step back in time and experience an original roadhouse built during the 1800's gold rush. Stagecoach rides, souvenir shop, restaurant, camping, cabins are all there to enjoy. You can even stay overnight in a covered wagon.

Historic Stays

We have unique accommodations in Wells, Barkerville, and Quesnel, for groups of two to 10. Suites for couples, or vacation homes for families, or other groups. Fun and interesting stays with 1930's decor and modern conveniences. Walking distance to trails,…

Inner Coast Inlet Tours

Inner Coast Inlet Tours is a sightseeing and water taxi operation. Based out of Bella Coola, we offer private boat charters to various locations on the central coast

Kopas Store

Make sure to stop into Kopas Store on your next visit to Bella Coola, offering a wide selection of locally-produced goods and products, plus supplies for the discerning sportsman. In addition to supplies, you'll also find indigenous jewellery, art, toys,…

Lakeside Motel

Great old-fashioned motel, offering quaint rooms with lovely views of Williams Lake. The Lakeside Motel offers 32 cozy, neat and clean rooms. Free newspapers, private yards, unlimited WiFi, public parking and coffee makers are also available to complete the home-away-from-home…

Lil'tem Mountain Hotel

From rainbow trout fishing in the nearby lakes, to exploring the hiking trails in the surrounding mountains, this small community offers a friendly and comfortable place to stay while enjoying the area. Also rich in St’át’imc Tsal’alh culture, Seton Portage…

Lillooet Museum & Visitor Centre

The Lillooet Museum & Visitor Centre is situated in downtown Lillooet in a former Anglican church. The original St. Mary's Church, which was torn down in 1960, stood on the same spot and arrived on the backs of miners and…

Marigold Fishing Resort

Located on the shores of Loon Lake just 4.5 hours from Vancouver, Marigold is pet friendly & a recipient of the TripAdvisor certificate of excellence. Our comfortable, lakefront cabins & RV's have fully equipped kitchens, hot & cold running water,…

Museum of the Cariboo Chilcotin

The Museum of the Cariboo Chilcotin hosts a collection of nearly 30,000 artifacts exhibiting the depth and breadth of the region's history. Stop by to view the western displays, including the largest saddle collection in Western Canada and the BC…

Nan Adventure Tours

Nan Adventure Tours offers hot springs charter tours, cultural tours, eco tours and water taxi services throughout Nuxalkulmc on the Central Coast of BC. Born and raised in Bella Coola and a member of the Nuxalk First Nation, Jason Moody…

Nemiah Valley Lodge

Nature as Created All-inclusive stays with the Xeni Gwet'in First Nation on Tsilhqot'in Title Lands. The Lodge and its seven cabins (each divisible into two units) offer Indigenous-inspired cuisine, modern accommodation in the newly renovated facilities and immersive cultural sharing…

Northern Lights Lodge

We are a full-service fly fishing lodge located deep in the Cariboo Mountains of BC, Canada. Our lakeside lodge is surrounded by multiple rivers and lakes on which we offer fully guided fly fishing adventures for both native rainbow trout…

Nusatsum River Guest House

Centrally Located in the Bella Coola Valley, 10 minutes east of Hagensborg, and 30 minutes west of Tweedsmuir Park Bear viewing station. With stunning views of the Coast Mountains you can relax in comfort on the decks, or take a…

Rainbow Resort

Open from May-September, we offer a range of cabins and camping to meet your needs! Come stay with us on beautiful Canim Lake and enjoy the serenity of the Cariboo.

Robert's Roost Resort

We welcome old and new visitors to enjoy this beautiful RV park and campground situated on the shores of Dragon Lake. The campground is located 10 minutes south of downtown Quesnel with a large selection of RV sites. Dragon Lake…

Shearwater Resort

Shearwater Resort is an Indigenous wilderness resort in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest that is owned and operated by Heiltsuk Nation. Shearwater Resort is on Denny Island, just a short water taxi ride from Bella Bella, British Columbia.…

Siwash Lake Wilderness Resort

This National Geographic Unique Lodge of the World is renowned as a top luxury wilderness resort, guest ranch, and eco-retreat. Here, guests can explore BC's backcountry by foot, mountain bike, canoe, helicopter, or horseback. Hone in on your love for…

Spirit Bear Lodge

In a land sculpted by the last ice age, where deep coastal fjords cut into the snow capped mountains and temperate rainforests lead to remote beaches, Spirit Bear Lodge takes visitors from around the world into the heart of the…

Station House Gallery

The Station House Gallery is located inside Williams Lake's oldest standing building, the historic Station house originally built in 1919 by the Pacific Great Eastern Railway. The Station House Gallery hosts rotating exhibitions in a variety of mediums by local,…

Sulphurous Lake Resort

You won’t find any sulphur here—what you will find is a spring-fed freshwater lake brimming with Trout, Kokanee, Burbot (freshwater cod) and Rainbow Trout. Our waters are also great for fishing, swimming, boating, water skiing, and more. As the only…

Tallheo Cannery Guest House

Discover Tallheo Cannery Guest House, set in the heart of Bella Coola. Surrounded by acres of coastal rainforest and private rocky beaches, this once thriving salmon cannery & community has been transformed into a unique experience for travellers. Experience one…

Three Nations Store & Lodge

THREE NATIONS STORE AND LODGE PROVIDES NEEDS FOR THE MODERN EXPLORER! Currently, the Store is the only facility within 55 km for visitors to purchase items. There is a gas station and restaurant and rustic accommodations for weary travellers. The…

Tweedsmuir Park Lodge

** Tweedsmuir Park Lodge is now climate positive! ** Nestled in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest, Tweedsmuir Park Lodge offers guests an authentic wilderness experience while enjoying world-class service. Just a short 70-minute flight from Vancouver (or 4.5hrs…

Wilderness Trails

Wilderness Trails facilitates conservation trips into the vast wilderness of the Chilcotin Ark. All our trips are based on our six principles of Nature Connection, Conservation and Stewardship, Personal Development, Self-Sufficiency, Empowerment and Conscious and Aware. Each and every wilderness…

Willow River Inn

The Willow is a second floor retreat in a unique heritage building centrally located in Wells. Intelligently arranged, large private space with an optional unique loft. Sleeping 2 to 10 people, it makes a fun base for winter or summer…

Xatsull Heritage Village

The Xatśūll First Nation community invites you to visit and experience their spiritual, cultural, and traditional way of life at their National, Award-Winning Heritage Village. There are regularly scheduled daily tours and you can take part in a variety of…